The experience of critical care encompasses a variety of stimuli and interventions that may interfere with normal sleep. The physical environment of a hospital room has been shown to be poorly suited for normal sleep. Constant background noise levels that frequently range between 60 and 80 dB and ambient light that frequently is not in phase with the patient’s normal light/dark cycle can interfere with a patient’s “internal body clock” or circadian rhythms. In addition, procedures and nursing care are generally performed without consideration of the time of day which can also disrupt sleep. Finally, the critical illness itself may disturb sleep through the experiences of pain, fear or central nervous system disturbance.

While a handful of studies have demonstrated circadian rhythm disturbances in patients on ventilators, the infrequent sampling of hormone levels to determine rhythmicity and the absence of concurrent polysomnography (sleep recording) have left a lot of unanswered questions. Dr. Gehlbach planned to definitively characterize the circadian rhythms and quality of sleep of acutely ill patients undergoing mechanical ventilation for respiratory failure. The first aspect of the project was to characterize the sleep quality and circadian rhythms of critically ill patients on a ventilator. All patients in the study were to undergo continuous polysomnography to determine sleep quality. It was expected that most patients will exhibit reduced and fragmented REM sleep patterns.

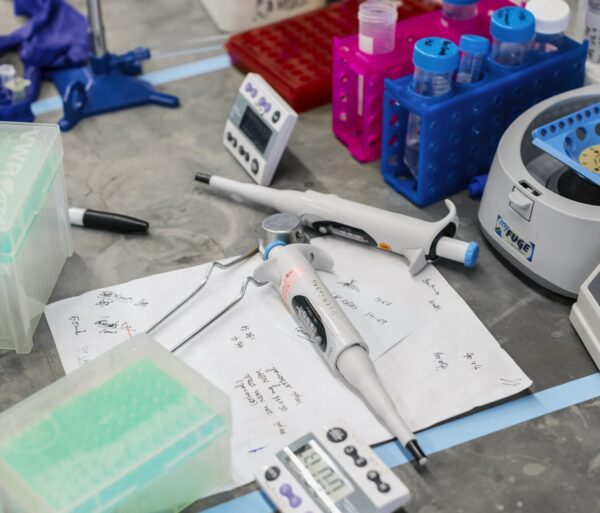

In addition, the levels of 6-sulfatoxymelatonin (the major metabolite of the pineal hormone melatonin) were to be measured at hourly intervals in order to assess circadian rhythmicity, which is expected to be disrupted. In addition to analyzing the patient’s sleep quality and circadian rhythm, Dr. Gehlbach and his colleagues manipulated the hospital room environment to promote better sleep by reducing noise, enforcing a normal light-dark cycle, and if possible performing nursing care according to time of day. This management of the environment worked to strengthen circadian rhythms and improve sleep quality.

The ultimate outcome of this study was to speed up recovery and lessen the duration of mechanical ventilation. It has been shown that the presence of delirium has been associated with adverse clinical outcomes, including longer hospital stay and increased six-month mortality for patients with respiratory failure. However, the role of sleep disruption in mediating delirium has not been investigated. If a relationship between disrupted sleep and delirium in critical illness was determined, doctors could utilize practical strategies that can be employed at the bedside to greatly impact a patient’s recuperation.

Dr. Gehlbach was confident that this previously neglected but extremely important area of research will generate results that are immediately applicable to the care of our sickest patients, and that something as simple as turning off the light at night may help save a life.